Gabapentin for the Treatment of Postherpetic Neuralgia

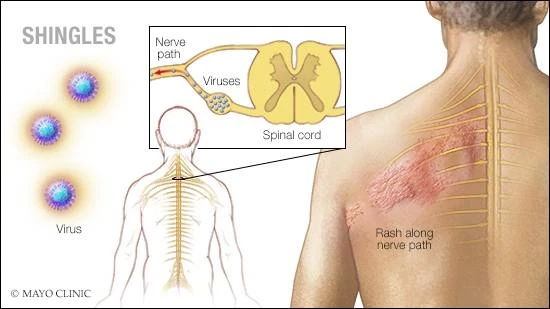

Postherpetic neuralgia (post-hur-PET-ik noo-RAL-juh) is the most common complication of shingles. The condition affects nerve fibers and skin, causing burning pain that lasts long after the rash and blisters of shingles disappear.

The chickenpox (herpes zoster) virus causes shingles. The risk of postherpetic neuralgia increases with age, primarily affecting people older than 60. There’s no cure, but treatments can ease symptoms. For most people, postherpetic neuralgia improves over time.

Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of postherpetic neuralgia are generally limited to the area of your skin where the shingles outbreak first occurred — most commonly in a band around your trunk, usually on one side of your body.

Signs and symptoms might include:

- Pain that lasts three months or longer after the shingles rash has healed. The associated pain has been described as burning, sharp and jabbing, or deep and aching.

- Sensitivity to light touch. People with the condition often can’t bear even the touch of clothing on the affected skin (allodynia).

- Itching and numbness. Less commonly, postherpetic neuralgia can produce an itchy feeling or numbness.

Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that adults 50 and older get a Shingrix vaccine to prevent shingles, even if they’ve had shingles or the older vaccine Zostavax. Shingrix is given in two doses, two to six months apart.

The CDC says two doses of Shingrix is more than 90 percent effective in preventing shingles and postherpetic neuralgia. Shingrix is preferred over Zostavax. The effectiveness may be sustained for a longer period of time than Zostavax. Zostavax may still be used sometimes for healthy adults age 60 and older who aren’t allergic to Zostavax and who don’t take immune-suppressing medications.

Gabapentin for the Treatment of Postherpetic Neuralgia

Context.— Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a syndrome of often intractable neuropathic pain following herpes zoster (shingles) that eludes effective treatment in many patients.

Objective.— To determine the efficacy and safety of the anticonvulsant drug gabapentin in reducing PHN pain.

Design.— Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel design, 8-week trial conducted from August 1996 through July 1997.

Setting.— Sixteen US outpatient clinical centers.

Participants.— A total of 229 subjects were randomized.

Intervention.— A 4-week titration period to a maximum dosage of 3600 mg/d of gabapentin or matching placebo. Treatment was maintained for another 4 weeks at the maximum tolerated dose. Concomitant tricyclic antidepressants and/or narcotics were continued if therapy was stabilized prior to study entry and remained constant throughout the study.

Main Outcome Measures.— The primary efficacy measure was change in the average daily pain score based on an 11-point Likert scale (0, no pain; 10, worst possible pain) from baseline week to the final week of therapy. Secondary measures included average daily sleep scores, Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Subject Global Impression of Change and investigator-rated Clinical Global Impression of Change, Short Form-36 (SF-36) Quality of Life Questionnaire, and Profile of Mood States (POMS). Safety measures included the frequency and severity of adverse events.

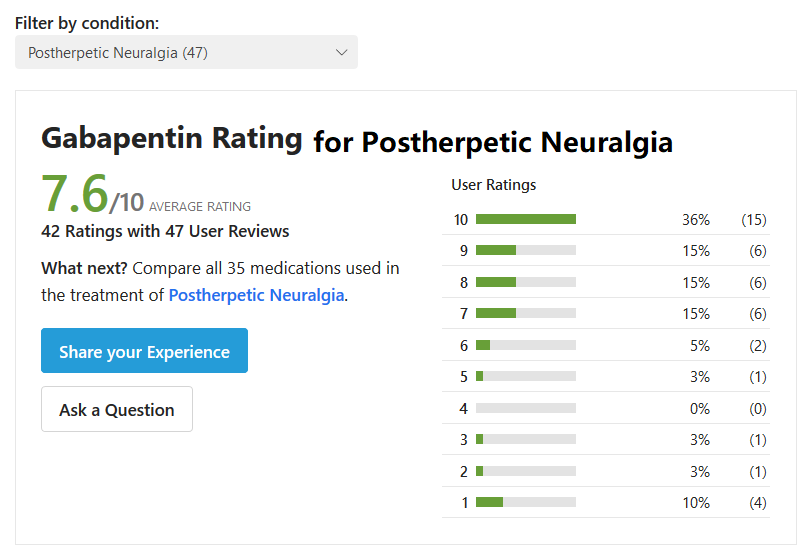

Results.— One hundred thirteen patients received gabapentin, and 89 (78.8%) completed the study; 116 received placebo, and 95 (81.9%) completed the study. By intent-to-treat analysis, subjects receiving gabapentin had a statistically significant reduction in average daily pain score from 6.3 to 4.2 points compared with a change from 6.5 to 6.0 points in subjects randomized to receive placebo (P<.001). Secondary measures of pain as well as changes in pain and sleep interference showed improvement with gabapentin (P<.001). Many measures within the SF-36 and POMS also significantly favored gabapentin (P≤.01). Somnolence, dizziness, ataxia, peripheral edema, and infection were all more frequent in the gabapentin group, but withdrawals were comparable in the 2 groups (15 [13.3%] in the gabapentin group vs 11 [9.5%] in the placebo group).

Conclusions.— Gabapentin is effective in the treatment of pain and sleep interference associated with PHN. Mood and quality of life also improve with gabapentin therapy.

Gabapentin for Postherpetic Neuralgia Comment

The results of our study clearly show that gabapentin reduces PHN pain compared with placebo. This was demonstrated on several measures of pain and as assessed by subjects as well as investigators. For the primary outcome variable, change in average daily pain score, the actual calculated power of the study in demonstrating the predicted level of efficacy of gabapentin approached 100%. In addition, several secondary outcome measures also showed gabapentin as superior to placebo. Sleep, several quality-of-life measures, and several mood state variables were significantly improved by gabapentin therapy. Significant improvement was evident during the titration phase (at the 2-week time period) and continued to accrue over the course of 8 weeks of treatment. Adverse effects of gabapentin were minor and well tolerated, consisting primarily of somnolence and dizziness. These 2 adverse effects accounted for most of the adverse event–related withdrawals. Despite doses of gabapentin up to 3600 mg/d in a population with an average age of 73 years, no serious drug-related adverse events were reported. In clinical practice, adverse effects such as these can be managed by a slower upward titration, dose reduction, and use of lower maximum doses than allowed in the clinical trial protocol. Serious adverse events, especially of a cardiovascular nature, were not evident. Overall, gabapentin reduced PHN pain with a very acceptable adverse effect profile.

The mechanism of action of gabapentin remains uncertain. Spinal cord neuronal calcium channels play a potentially important role in chronic neuropathic pain and are modulated by gabapentin. Analgesia through GABAergic neurotransmission effects is much less certain. Despite the uncertainty regarding the mechanism of action of gabapentin, the drug has been shown effective in rat models of chronic neuropathic pain.22-25 Results of treatment of PHN can likely be predicted by testing in preclinical neuropathic pain models because PHN is not only common, but has consistent symptomatology, a clear cause, and consistent neuropathology.

The current standard of treatment for PHN with oral medications are the TCAs. Nontricyclic antidepressants with better adverse effect and safety profiles, including the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, have not been proven equivalent to TCAs in terms of efficacy.16 In the elderly population afflicted with PHN, therapy with TCAs is frequently either contraindicated (usually for cardiovascular reasons) or poorly tolerated because of excessive sedation, cognitive impairment, dry mouth, constipation, sexual dysfunction, and orthostatic lightheadedness. Other approaches with good safety and evidence of efficacy, such as topical local anesthetics and topical aspirin-nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, are either unproven in long-term use or not commercially available.2 Topical capsaicin produces a modest improvement in pain after long-term use, but has a high rate of burning sensations that are unacceptably severe.1 Opioids are frequently used to treat PHN in clinical practice, but do not yet have adequate support from placebo-controlled studies of long-term use. Many of the problematic adverse effects of TCAs also pertain to the use of opioids, such as sedation, cognitive impairment, and constipation. In addition, many patients and physicians are reluctant to use medications that carry the stigma of being addicting, despite the lack of evidence that this is a problem in the PHN population.

From the safety and efficacy evidence in our study, a strong case can be made for considering gabapentin as a first-line oral medication for management of PHN pain. There are no studies directly comparing gabapentin with TCAs. From published systematic reviews of antidepressants and anticonvulsants for neuropathic pain by McQuay et al,32 comparisons of safety and efficacy can be made by calculating the number needed to treat (NNT) for both parameters. The NNT is the reciprocal of the difference in the percentage of patients improved or harmed by active therapy compared with control therapy, expressed for benefit as 1/[(% improved active)−(% improved placebo)]. For placebo-controlled TCA studies of PHN pain, the NNT for benefit ranged from 1.9 to 4.1; for minor adverse events, the NNT ranged from 1.7 to 8.8; and for adverse events leading to study withdrawal, the NNT ranged from 13 to 37. From the data in Figure 4 and the text, the gabapentin NNT for benefit is 3.2, the NNT for minor adverse events is 3.7, and the NNT for adverse events leading to study withdrawal is 25. From this perspective, gabapentin should be considered at least as effective as TCAs, at least as safe, and with fewer contraindications to use.

Tricyclic antidepressants and opioids each have a different mechanism of action than gabapentin. Tricyclic antidepressants may relieve pain through serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake blockade, by blockade of α-adrenergic receptors, by sodium channel-blocking effects, and by relief of depression. Opioids relieve pain through activation of a family of specific receptors found in both the central and peripheral nervous systems.

Because of its straightforward pharmacokinetics and relative lack of adverse drug interactions, multidrug regimens to control chronic neuropathic pain can include gabapentin if gabapentin monotherapy fails. In summary, based on the results of this 8-week study, gabapentin can be added to the list of first-line medications for treatment of chronic neuropathic pain syndromes such as PHN.

Related posts:

- Gabapentin For Pain

- What Is Gabapentin Off Label Usages ?

- What is Gabapentin Used for ? What is the Off-Label Usages of Gabapentin ?

- Treatment Effects of Gabapentin for Primary Insomnia

- Who Can not Buy Gabapentin Online ?

- Gabapentin Dosage

- Gabapentin is Widely Used for Neuropathic Pain and Postherpetic Neuralgia

- Geriatric Use and Pediatric Use of Gabapentin for Neuropathic Pain

- Gabapentin Side Effects

- What Serious Side Effects May Happen if I Stop Taking Gabapentin and How to treat Gabapentin Withdrawal

- Is Gabapentin Addictive or Dependence ?

- Is Gabapentin an Opiate?

Neurontin (gabapentin): “I had an accident and broke my leg in half and had to be life flighted to Pittsburgh hospital. I live in West Virginia. They wanted to amputate my leg but I said no and ended up with 15 surgeries and 20 pins. I am disabled due to it but I have my leg.

The pain was the worst I have ever felt. I was on oxycontin 40 MG 3 x day with 30 MG oxycodone 8 x daily instant release tabs,with neurontin as well. But as I was wean down on pain meds I was left with neurontin.

I have severe nerve damage to my whole leg. I’m on two 400 MG tabs 3 x daily. So 2400 MG total daily. I will be on for rest of my life. It is made my life so much better.

I can walk without pain but sleep is rough with nite terror for me. But short of that I would recommend it for nerve damage. It helps me function mentally as well. It’s great!”

I was given gabapentin for shingles nerve pain. If I take 100 mg I go to sleep. I only take 50 mg a day. Everybody is different on this drug, and if you are having side effects, and a doctor is telling you to keep taking it…I would either lower the dosage and or get a second opinion.

Too many drugs are given out at a dose that somebody said is “the norm”. Well, we are each unique. If you are ever uncomfortable or having bad side effects I would read up on the drug, and talk to you doc again, and….in the end, only you know exactly how you feel.

If side effects are not getting better, not going away, and they are interfering too much in your life, not the correct drug or dose for you.

Was given medicine for itching due to shingles. Within 3 days of taking it developed sore throat then coughing, runny nose and sneezing. Doctor claimed it was not from medicine but these side effects are listed. Very miserable to deal with pain of shingles and then this.