What is restless legs syndrome?

Restless legs syndrome (RLS), also called Willis-Ekbom Disease, causes unpleasant or uncomfortable sensations in the legs and an irresistible urge to move them. Symptoms commonly occur in the late afternoon or evening hours, and are often most severe at night when a person is resting, such as sitting or lying in bed.

They also may occur when someone is inactive and sitting for extended periods (for example, when taking a trip by plane or watching a movie). Since symptoms can increase in severity during the night, it could become difficult to fall asleep or return to sleep after waking up. Moving the legs or walking typically relieves the discomfort but the sensations often recur once the movement stops. RLS is classified as a sleep disorder since the symptoms are triggered by resting and attempting to sleep, and as a movement disorder, since people are forced to move their legs in order to relieve symptoms. It is, however, best characterized as a neurological sensory disorder with symptoms that are produced from within the brain itself.

RLS is one of several disorders that can cause exhaustion and daytime sleepiness, which can strongly affect mood, concentration, job and school performance, and personal relationships. Many people with RLS report they are often unable to concentrate, have impaired memory, or fail to accomplish daily tasks. Untreated moderate to severe RLS can lead to about a 20 percent decrease in work productivity and can contribute to depression and anxiety. It also can make traveling difficult.

It is estimated that up to 7-10 percent of the U.S. population may have RLS. RLS occurs in both men and women, although women are more likely to have it than men. It may begin at any age. Many individuals who are severely affected are middle-aged or older, and the symptoms typically become more frequent and last longer with age.

More than 80 percent of people with RLS also experience periodic limb movement of sleep (PLMS). PLMS is characterized by involuntary leg (and sometimes arm) twitching or jerking movements during sleep that typically occur every 15 to 40 seconds, sometimes throughout the night. Although many individuals with RLS also develop PLMS, most people with PLMS do not experience RLS.

Fortunately, most cases of RLS can be treated with non-drug therapies and if necessary, medications.

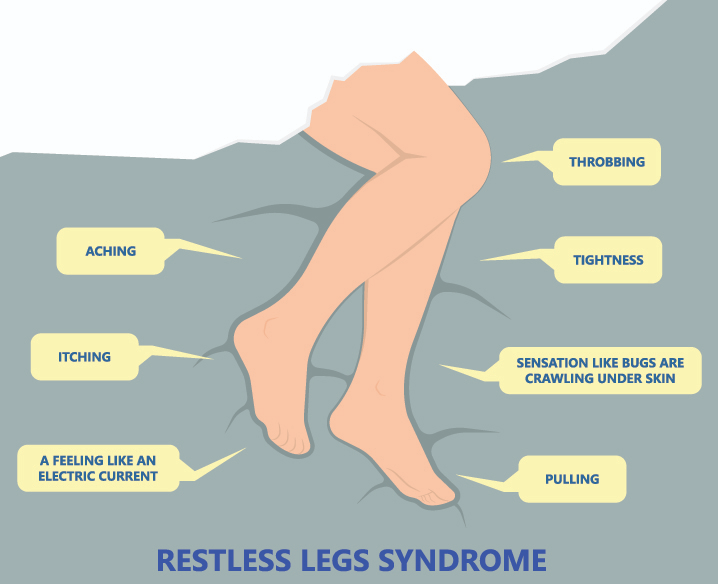

What are common signs and symptoms of restless legs?

People with RLS feel the irresistible urge to move, which is accompanied by uncomfortable sensations in their lower limbs that are unlike normal sensations experienced by people without the disorder. The sensations in their legs are often difficult to define but may be described as aching throbbing, pulling, itching, crawling, or creeping. These sensations less commonly affect the arms, and rarely the chest or head. Although the sensations can occur on just one side of the body, they most often affect both sides. They can also alternate between sides. The sensations range in severity from uncomfortable to irritating to painful.

Because moving the legs (or other affected parts of the body) relieves the discomfort, people with RLS often keep their legs in motion to minimize or prevent the sensations. They may pace the floor, constantly move their legs while sitting, and toss and turn in bed.

A classic feature of RLS is that the symptoms are worse at night with a distinct symptom-free period in the early morning, allowing for more refreshing sleep at that time. Some people with RLS have difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. They may also note a worsening of symptoms if their sleep is further reduced by events or activity.

RLS symptoms may vary from day to day, in severity and frequency, and from person to person. In moderately severe cases, symptoms occur only once or twice a week but often result in significant delay of sleep onset, with some disruption of daytime function. In severe cases of RLS, the symptoms occur more than twice a week and result in burdensome interruption of sleep and impairment of daytime function.

People with RLS can sometimes experience remissions—spontaneous improvement over a period of weeks or months before symptoms reappear—usually during the early stages of the disorder. In general, however, symptoms become more severe over time.

People who have both RLS and an associated medical condition tend to develop more severe symptoms rapidly. In contrast, those who have RLS that is not related to any other condition show a very slow progression of the disorder, particularly if they experience onset at an early age; many years may pass before symptoms occur regularly.

What causes restless legs syndrome?

In most cases, the cause of RLS is unknown (called primary RLS). However, RLS has a genetic component and can be found in families where the onset of symptoms is before age 40. Specific gene variants have been associated with RLS. Evidence indicates that low levels of iron in the brain also may be responsible for RLS.

Considerable evidence also suggests that RLS is related to a dysfunction in one of the sections of the brain that control movement (called the basal ganglia) that use the brain chemical dopamine. Dopamine is needed to produce smooth, purposeful muscle activity and movement. Disruption of these pathways frequently results in involuntary movements. Individuals with Parkinson’s disease, another disorder of the basal ganglia’s dopamine pathways, have increased chance of developing RLS.

RLS also appears to be related to or accompany the following factors or underlying conditions:

- end-stage renal disease and hemodialysis

- iron deficiency

- certain medications that may aggravate RLS symptoms, such as antinausea drugs (e.g. prochlorperazine or metoclopramide), antipsychotic drugs (e.g., haloperidol or phenothiazine derivatives), antidepressants that increase serotonin (e.g., fluoxetine or sertraline), and some cold and allergy medications that contain older antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine)

- use of alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine

- pregnancy, especially in the last trimester; in most cases, symptoms usually disappear within 4 weeks after delivery

- neuropathy (nerve damage).

Sleep deprivation and other sleep conditions like sleep apnea also may aggravate or trigger symptoms in some people. Reducing or completely eliminating these factors may relieve symptoms.

How is restless legs syndrome diagnosed?

Since there is no specific test for RLS, the condition is diagnosed by a doctor’s evaluation. The five basic criteria for clinically diagnosing the disorder are:

- A strong and often overwhelming need or urge to move the legs that is often associated with abnormal, unpleasant, or uncomfortable sensations.

- The urge to move the legs starts or get worse during rest or inactivity.

- The urge to move the legs is at least temporarily and partially or totally relieved by movements.

- The urge to move the legs starts or is aggravated in the evening or night.

- The above four features are not due to any other medical or behavioral condition.

A physician will focus largely on the individual’s descriptions of symptoms, their triggers and relieving factors, as well as the presence or absence of symptoms throughout the day. A neurological and physical exam, plus information from the person’s medical and family history and list of current medications, may be helpful. Individuals may be asked about frequency, duration, and intensity of symptoms; if movement helps to relieve symptoms; how much time it takes to fall asleep; any pain related to symptoms; and any tendency toward daytime sleep patterns and sleepiness, disturbance of sleep, or daytime function. Laboratory tests may rule out other conditions such as kidney failure, iron deficiency anemia (which is a separate condition related to iron deficiency), or pregnancy that may be causing symptoms of RLS. Blood tests can identify iron deficiencies as well as other medical disorders associated with RLS. In some cases, sleep studies such as polysomnography (a test that records the individual’s brain waves, heartbeat, breathing, and leg movements during an entire night) may identify the presence of other causes of sleep disruption (e.g., sleep apnea), which may impact management of the disorder. Periodic limb movement of sleep during a sleep study can support the diagnosis of RLS but, again, is not exclusively seen in individuals with RLS.

Diagnosing RLS in children may be especially difficult, since it may be hard for children to describe what they are experiencing, when and how often the symptoms occur, and how long symptoms last. Pediatric RLS can sometimes be misdiagnosed as “growing pains” or attention deficit disorder.

How is restless legs syndrome treated?

RLS can be treated, with care directed toward relieving symptoms. Moving the affected limb(s) may provide temporary relief. Sometimes RLS symptoms can be controlled by finding and treating an associated medical condition, such as peripheral neuropathy, diabetes, or iron deficiency anemia.

Iron supplementation or medications are usually helpful but no single medication effectively manages RLS for all individuals. Trials of different drugs may be necessary. In addition, medications taken regularly may lose their effect over time or even make the condition worse, making it necessary to change medications.

Treatment options for RLS include:

Lifestyle changes. Certain lifestyle changes and activities may provide some relief in persons with mild to moderate symptoms of RLS. These steps include avoiding or decreasing the use of alcohol and tobacco, changing or maintaining a regular sleep pattern, a program of moderate exercise, and massaging the legs, taking a warm bath, or using a heating pad or ice pack. There are new medical devices that have been cleared by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA), including a foot wrap that puts pressure underneath the foot and another that is a pad that delivers vibration to the back of the legs. Aerobic and leg-stretching exercises of moderate intensity also may provide some relief from mild symptoms.

Iron. For individuals with low or low-normal blood tests called ferritin and transferrin saturation, a trial of iron supplements is recommended as the first treatment. Iron supplements are available over-the-counter. A common side effect is upset stomach, which may improve with use of a different type of iron supplement. Because iron is not well-absorbed into the body by the gut, it may cause constipation that can be treated with a stool softeners such as polyethylene glycol. In some people, iron supplementation does not improve a person’s iron levels. Others may require iron given through an IV line in order to boost the iron levels and relieve symptoms.

Anti-seizure drugs. Anti-seizure drugs are becoming the first-line prescription drugs for those with RLS. The FDA has approved gabapentin enacarbil for the treatment of moderate to severe RLS, This drug appears to be as effective as dopaminergic treatment (discussed below) and, at least to date, there have been no reports of problems with a progressive worsening of symptoms due to medication (called augmentation). Other medications may be prescribed “off-label” to relieve some of the symptoms of the disorder.

Other anti-seizure drugs such as the standard form of gabapentin and pregabalin can decrease such sensory disturbances as creeping and crawling as well as nerve pain. Dizziness, fatigue, and sleepiness are among the possible side effects. Recent studies have shown that pregabalin is as effective for RLS treatment as the dopaminergic drug pramipexole, suggesting this class of drug offers equivalent benefits.

Dopaminergic agents. These drugs, which increase dopamine effect, are largely used to treat Parkinson’s disease. They have been shown to reduce symptoms of RLS when they are taken at nighttime. The FDA has approved ropinirole, pramipexole, and rotigotine to treat moderate to severe RLS. These drugs are generally well tolerated but can cause nausea, dizziness, or other short-term side effects. Levodopa plus carbidopa may be effective when used intermittently, but not daily.

Although dopamine-related medications are effective in managing RLS symptoms, long-term use can lead to worsening of the symptoms in many individuals. With chronic use, a person may begin to experience symptoms earlier in the evening or even earlier until the symptoms are present around the clock. Over time, the initial evening or bedtime dose can become less effective, the symptoms at night become more intense, and symptoms could begin to affect the arms or trunk. Fortunately, this apparent progression can be reversed by removing the person from all dopamine-related medications.

Another important adverse effect of dopamine medications that occurs in some people is the development of impulsive or obsessive behaviors such as obsessive gambling or shopping. Should they occur, these behaviors can be improved or reversed by stopping the medication.

Opioids. Drugs such as methadone, codeine, hydrocodone, or oxycodone are sometimes prescribed to treat individuals with more severe symptoms of RLS who did not respond well to other medications. Side effects include constipation, dizziness, nausea, exacerbation of sleep apnea, and the risk of addiction; however, very low doses are often effective in controlling symptoms of RLS.

Benzodiazepines. These drugs can help individuals obtain a more restful sleep. However, even if taken only at bedtime they can sometimes cause daytime sleepiness, reduce energy, and affect concentration. Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam and lorazepam are generally prescribed to treat anxiety, muscle spasms, and insomnia. Because these drugs also may induce or aggravate sleep apnea in some cases, they should not be used in people with this condition. These are last-line drugs due to their side effects.

What is the prognosis for people with restless legs syndrome?

RLS is generally a lifelong condition for which there is no cure. However, current therapies can control the disorder, minimize symptoms, and increase periods of restful sleep. Symptoms may gradually worsen with age, although the decline may be somewhat faster for individuals who also suffer from an associated medical condition. A diagnosis of RLS does not indicate the onset of another neurological disease, such as Parkinson’s disease. In addition, some individuals have remissions—periods in which symptoms decrease or disappear for days, weeks, months, or years—although symptoms often eventually reappear. If RLS symptoms are mild, do not produce significant daytime discomfort, or do not affect an individual’s ability to fall asleep, the condition does not have to be treated.

What research is being done?

The mission of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke is to seek fundamental knowledge about the brain and nervous system and to use that knowledge to reduce the burden of neurological disease. The NINDS is a component of the National Institutes of Health , the leading supporter of biomedical research in the world.

While the direct cause of RLS is often unknown, changes in the brain’s signaling pathways are likely to contribute to the disease. In particular, researchers suspect that impaired transmission of dopamine signals in the brain’s basal ganglia may play a role. There is a relationship between genetics and RLS. However, currently there is no genetic testing. NINDS-supported research is ongoing to help discover genetic relationships and to better understand what causes the disease.

The NINDS also supports research on why the use of dopamine agents to treat RLS, Parkinson’s disease, and other movement disorders can lead to impulse control disorders, with aims to develop new or improved treatments that avoid this adverse effect.

The brain arousal systems appear to be overactive in RLS and may produce both the need to move when trying to rest and the inability to maintain sleep. NINDS-funded researchers are using advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure brain chemical changes in individuals with RLS and evaluate their relation to the disorder’s symptoms in hopes of developing new research models and ways to correct the overactive arousal process. Since scientists currently don’t fully understand the mechanisms by which iron gets into the brain and how those mechanisms are regulated, NINDS-funded researchers are studying the role of endothelial cells—part of the protective lining called the blood-brain barrier that separates circulating blood from the fluid surrounding brain tissue—in the regulation of cerebral iron metabolism. Results may offer new insights to treating the cognitive and movement symptoms associated with these disorders.

More information about research on RLS supported by NINDS or other components of the NIH is available through the NIH RePORTER (http://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm), a searchable database of current and previously funded research, as well as research results such as publications.